Europe’s data rule shake-up: How companies are dealing with it

From Berlin to Paris and Brussels, computer developers and company executives are attempting to thrash out the implications of sweeping new data protection rules that will come into force in the EU in May. At day-long workshops with lawyers and regulators, companies including Facebook, SoundCloud and the Financial Times have experimented with solutions for the 88 pages of new rules, which present the biggest challenge yet to the runaway growth of personal data collection.

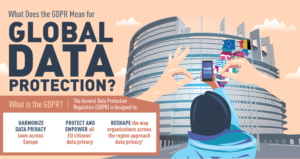

The EU’s General Data Protection Regulation will apply in all member states from May 25 and involves major changes to the way businesses are allowed to collect, store and make money from data in a market that is worth €59.5bn, according to data provider IDC. The rules affect everything from how companies report hacks and other data losses, to customer consent and “the right to be forgotten”, where an individual can ask for their data to be deleted if there is no “compelling” reason for it to be retained. They require businesses to make changes as wide-ranging and fundamental as how they organise information and as detailed as the size of the letters they use to describe terms and conditions.

“It is a huge design and learning process,” said Stephen Deadman, global deputy chief privacy officer of Facebook, which has assembled its biggest-ever cross-functional team to deal with the rules, at an expected cost of several million dollars. “What I’d like to say is that we’re going to be compliant in May, but it has to be an ongoing process.” The prospect of huge fines for breaches makes GDPR an issue that company boards are involved in: regulators will have the power to penalise businesses €20m or up to 4 per cent of their previous year’s global turnover, whichever is higher, for breaking the rules. With 141 days remaining, here are the main areas companies are considering in their preparations.

CONSENT

Mapstr is a map-based app that allows users to bookmark locations such as friends’ houses or favourite restaurants, so they can return to them later. Founded in France three years ago, it relies on people sharing this information to create networks. Under GDPR, companies such as Mapstr will have to ask for explicit consent for each use of personal information, and will not be able to rely on consent in the form of “silence, pre-ticked boxes or inactivity”. Users must be able to withdraw consent and delete information from servers and friends’ phones if they change their minds.

According to Sébastien Caron, Mapstr’s founder, the changes will affect even the size of the font on the app. After speaking to experts at Facebook’s brainstorming session in Paris, he decided that the text allowing users to refuse consent should be the same size as the option for accepting. “This is mostly about helping the user believe that we respect the regulation . . . because almost no one understands it,” he said. “They feel safer because they see that by default they don’t have to give access and have full control.”

Bigger companies that use data in many different ways could face problems if full transparency alarms users. If people understood the way Facebook uses personal data to sell adverts not just on its own site, but also across the internet, would they agree? Uber shocked the world last month when it revealed it had deliberately concealed a major data breach that compromised the information of 57m of its customers and drivers around the world.

EU data protection authorities launched a co-ordinated investigation in response, but any penalty in Europe will be extremely limited under current data protection rules. Under GDPR, the rules will be much tougher. Far-reaching new requirements on cyber security require companies to report breaches to regulators within 72 hours of their discovery. According to cyber security experts, companies are often not even aware of attacks. “When companies have suffered breaches it is a progressive process, it is not like suddenly someone in IT looks at the logs and says we have just been hacked, or realises that data has been stolen overnight,” said Eduardo Ustaran, a privacy and data protection lawyer at Hogan Lovells.

Most corporate victims will not want to announce a cyber security breach until they have patched the hole, to prevent other hackers using the same vulnerability. Yassir Abousselham, chief security officer at Okta, the ID security company, said there was a “grey area” where companies tried to inform regulators without alerting the public. “When any breach is made public these days, it tends to attract a lot more attackers, essentially sharks who smell blood,” he said.